Portable Magic

Reading, for me, is entertainment and an escape from the real world. But it can also inform and stretch the boundaries of the life I live.

Currently reading

Invisible Man - 21%

I started this audio during my long drive this weekend and MY GOD my jaw was dropped through most of it. Everything about Joe Morton's performance just floored me.

The downside is that it's so dense with ideas and imagery and emotion that there is no way I can continue it solely on audio, since I'm normally listening while I multitask doing other things, so I won't have the luxury of staring blankly at a highway while spending 90% of my attention on what's soaking into my brain through my ears. Plus, I want to be able to stop and consider what I'm reading, and to look up some of the references.

So I've put the ebook on hold at the library, and will suspend the audio until my hold comes up and I can both read and listen to this together. Hopefully it'll only be a couple of weeks.

3

3

4

4

The Bungalow Mystery - update ND3.9

Artwork Comparison

The changing artwork is part of my fun in collecting these books. Although there are two text versions, the illustrations were updated three times, with the quality deteriorating each time.

Russell Tandy did the first two versions, but the second revision, to save costs on the printing, only included a single frontispiece in a plain paper rather than glossy page, and for this book was an entirely new scene. The book in my collection with this illustration was printed about 1952, but based on Nancy’s hair and clothes, I’m guessing that this illustration was done in the 40’s. Here are an example of the original and revised Tandy illustrations, the first showing Nancy breaking into Jacob’s house, and the second showing Nancy and the rescued Jacob finding his house ransacked and empty:

The illustrations were revised again for the 1959 revised text, but this time by an uncredited artist who had little of Tandy’s talent, and by the 1970’s (for the later volumes in the series) the illustrations look like they were pulled from a reject pile of scribblings. The revised versions all have 6 plain paper line drawings. These revised text illustrations don’t attempt to mirror Tandy’s original work, although they sometimes show a similar scene.

The stormy lake:

The tree blocking the road:

And last, here’s an illustration of my favorite scene in the original, that never would have made it into the revision, where Nancy parks illegally, rushes into a hotel lobby, snatches the phone from the desk clerk, then proceeds to give him orders to start making phone calls for her.

Index of Posts:

ND3.1 1930 Chs 1-3 vs 1960 Chs 1-2

ND3.2 1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

ND3.3 1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

ND3.4 1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

ND3.5 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

ND3.6 1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

ND3.7 1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

8

8

1

1

The Bungalow Mystery - update ND3.8

1930 Chs 22-25 vs 1960 Ch 18-20

Both versions conclude the events with a bang. Literally.

1930 Nancy just happens to meet up with her father as she’s racing to catch up to Stumpy and Mr. Drew and Laura are racing to find Nancy. After syncing their stories, the chase continues with Mr. Drew instructing Laura to get in the roadster with Nancy, saying, “If it comes to a battle, you girls can drop back and be out of range of the bullets.” (me: !!!!!)

Nancy takes off ahead of her father like the speed demon that she is. The next few paragraphs are an ode to the power of Nancy‘s little roadster and the skill of her driving. Nancy Drew gives no f***s for your speed limit; she drives as fast as she thinks she can without wrecking.

“Her eyes focused upon the road, Nancy Drew clung grimly to the wheel. The little figured ribbon in the speedometer crept higher and higher until the car wavered in the road. Reducing the speed slightly, she held her foot steady on the gasoline pedal.”

They catch up to Stumpy and Nancy drops back to let Mr. Drew engage him in a gun fight while still driving at top speed.

“Nancy sensed that the end was drawing near, for it was apparent that the racing car had reached its maximum speed. Stumpy was making his last stand, and knew it. He looked back over his shoulder frequently now. Nancy had never seen such reckless driving. Where would the mad race end?”

They come up on a sharp curve and a cliff. Nancy and her father see it in enough time that with their skillful driving they’re able to stop, but Stumpy Dowd, being a villain and a reckless driver, goes right over the barrier and over the cliff.

Scrambling down into the ravine, they find Stumpy alive but pinned beneath the wreck. They’re able to drag him free as the car catches fire. Nancy, knowing that Laura’s fortune is in the burning car, dives back in and retrieves two suitcases. Her father yanks her back just before the car explodes.

The 1960 chase and capture is more convoluted and not nearly as exciting, partly due to the added embezzlement subplot and related characters. They drive around to more places, Mr. Drew gets conked on the head by one of the baddies, so Nancy is driving for the chase scene, but it ends the same way, with the crash and explosion.

The last couple of chapters wrap up the story, with the villains surviving so they can go to jail for a satisfactorily long time, Laura and her fortune reunited with her real guardian and his fortune, and everyone praises Nancy’s cleverness and courage, while Nancy wonders what her next adventure will be.

Considerations – Violence and risk:

I guess the 1960 revision might have been exciting for readers who had never experienced the glorious original. But there’s no way the 1960 sanitized versions were going to include a complete disregard for speed limits, a Bonnie and Clyde style gun battle, the contemplation of finding gruesomely injured people in the wrecked car, or sensible Nancy crawling into a burning car for money. 1960 Nancy can’t even be considered even peripherally responsible for the wreck, since she had just caught sight of Stumpy’s car before it went over the cliff. Technically speaking, there wasn’t even a car chase.

One side note: in keeping with her impulsive and non-law-abiding nature, 1930 Nancy actually withholds the information about Jacob Aborn’s kidnapping from the police, just because Laura is present. She wants to surprise Laura by introducing her directly to her real guardian, and doesn’t want it spoiled by the police report.

Index of Posts:

ND3.1 1930 Chs 1-3 vs 1960 Chs 1-2

ND3.2 1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

ND3.3 1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

ND3.4 1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

ND3.5 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

ND3.6 1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

ND3.7 1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

6

6

5

5

Sycamore Row - 0%

Oh boy, I am in a real audiobook reading funk. I have almost a hundred acquired audios waiting to be read and can't work up a real interest in any of them. I just DNF'd an Audible monthly freebie that isn't in the catalog here and I'm too lazy to add.

So, since I re-read A Time To Kill recently, and this sequel was available immediately at the library, I'm going to give it a shot.

Fingers crossed!

5

5

1

1

The Bungalow Mystery - update ND3.7

1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

These chapters offer the greatest contrast between the original and revision storytelling styles, as they cover Nancy’s escape from the bungalow and pursuit of the fleeing Stumpy Dowd.

Abandoned to starve in the basement, Nancy keeps her head and methodically sets about trying to free herself, working at the ropes to loosen them enough to get out. She’s able to unchain Jacob Aborn because, in typical Scooby Doo criminal fashion, Stumpy left the key to the padlock behind in plain sight to torment them. The fiend!

At this point, the versions diverge as Nancy is rewritten to be more restrained, more dependent on law and the menfolk, and to add a lot of convoluted plot elements and accommodate all the unnecessary new characters.

1930 Nancy helps the debilitated Jacob back to his house, finding it ransacked with Stumpy gone with all of Laura’s money and all of Jacobs money. There is no phone at the cottage. Jacob is too weak to go further so Nancy leaves him here and takes off to get him a doctor, notify the police, and pursue Jacob.

“The rough forest road held Nancy to a slow pace, but when she reached the lake thoroughfare she stepped on the accelerator, and the little car begin to purr like a contented cat.”

What happens next is pure 1930 Nancy and had no chance of making it into the 1960 revision. When Nancy gets to the fancy hotel, she parks illegally, storms into the lobby looking like a wild woman with her hair in disorder and her clothing in disarray, and seeing that the telephone booths are all in use, she sprints to the main desk and snatches up the clerk’s private telephone. Everyone there is scandalized, but Nancy couldn’t care less.

She tries phoning home to warn them but nobody is there. She has hotel clerk start calling all the police stations between there and River Heights and also the radio stations asking them to put out public alert before running back out and haring off after Stumpy. I have no idea if the radio stations would do such a thing in 1930, but they certainly wouldn’t do it today.

Back home in River Heights, Laura has been worrying about Nancy all day, and when Mr. Drew gets in from out of town and learns what Nancy is up to, he loads his revolver and races off to find her, taking Laura with him.

1960 Nancy also helps the debilitated Jacob back to his ransacked house, but is stuck there because Stumpy has disabled her car and cut the phone lines. Then suddenly all the extra characters show up and the plots all converge: Mr. Drew, Laura, and Nancy’s ex-boyfriend Don arrive, then the Donnell kids that helped Nancy with the fallen tree way back in Ch. 4 show up with their parents and everyone sits around talking and giving complicated explanations of bank embezzlement and people calling each other and misunderstandings, etc. Nancy puts all these clues together with her own story and everyone is amazed and admiring at her bravery and cleverness. The police are called, and Mr. Drew’s good buddy the River Heights police chief sets a patrol car and 4 men to guard the Drews home. I guess the 1960s were nice if you were a rich prominent citizen.

Considerations – Violence and gore:

The 1960 revision continues to tame down the more exciting and explicit elements into blandness. Although both Nancys calmly work to get loose of the ropes, the 1930 version describes her abraded and bleeding wrists and the original Jacob rages against his chains and vainly tries to break the padlock against the cellar floor. When 1930 Mr. Drew discovers that his daughter may be in danger, he loads and pockets his revolver before dashing off in his sedan, but 1960 Mr. Drew is just so worried that “he could barely restrain himself from breaking the speed limit”.

Considerations – Active vs passive plot events:

This part of the story is very action-oriented in the 1931 original. We follow along with Nancy’s thoughts as she puts clues together and rushes wildly to stop Stumpy Dowd. The 1961 revision is far more static, where people gather in one place and explain to one another how the various plot elements fit. The reader doesn’t know that Nancy has even put it all together until she tells her admiring audience.

Dated Plot Points - Telephones:

Again, much of the plot depends on an inability to communicate with others or call for help. Even Nancy’s flashlight battery problem would have been solved with an iPhone. A modern retelling of this story would have to depend on a mobile phone getting broken or being out of service range.

The Cult of Domesticity – Nancy is smart but testicles take charge:

The 1931 Nancy does not wait around for help from anyone. She charges about and gives orders to everyone – Jacob, the hotel clerk, the radio stations, the police. 1961 Nancy is just as smart – we are even told that she had taken a class in auto mechanics and so was able to look under the hood of her convertible and figure out how Stumpy had tampered with it. But when her father and the police show up, she steps back and lets them make the decisions and lead the discussion. She offers her input, but makes suggestions and asks about taking action rather than just doing it.

The Cult of Domesticity – Laura is girly and Hannah is motherly:

1931 Laura spends her day worrying about Nancy, chafing at the inaction and unable to distract herself, but 1961 Laura happily goes off to a BBQ with Nancy’s ex-boyfriend and has a lovely time socializing. 1931 Hannah the housekeeper is an almost invisible servant, but 1961 Hannah has motherly concern for Nancy’s safety and frets over her continuously, when she’s not in the kitchen cooking up and serving yummy things to eat.

Index of Posts:

ND3.1 1930 Chs 1-3 vs 1960 Chs 1-2

ND3.2 1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

ND3.3 1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

ND3.4 1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

ND3.5 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

ND3.6 1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

ND3.7 1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

7

7

3

3

Longbourn ★★★★☆

This was a terrific first-half read. The back half lost some steam and I lost some of my buy-in to plot and characters. What was a fascinating look at what life might have been like for the servants propping up the various featured characters and households in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice became a meandering and increasingly unlikely story.

Still an enjoyable read and the first 2/3 of it was absolutely worthwhile. Certainly better than any other Jane Austen fan-fic type stories I've picked up.

Audiobook, borrowed from my public library via Overdrive. Excellent performance by Emma Fielding.

14

14

5

5

The Bungalow Mystery - update ND3.6

1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

We finally get to the eponymous bungalow of these two books as Nancy continues her snooping, makes a big discovery, and gets caught by the bad guy. These chapters are pretty similar, but Nancy’s updated (more boring) personality saps much of the fun melodrama from it.

Once Stumpy goes to bed, 1930 Nancy can finally creep out of hiding and check out the decrepit bungalow with her now-dying flashlight. It’s disappointingly empty until she opens the basement door and sees Jacob Aborn, which sends her into a full panic stumbling around in the dark until she finally gets out of the cottage and then finally starts to think. Panic over, she realizes that the person in the basement couldn’t possibly be Jacob and goes back to check it out. Nancy finds a man who looks like Jacob chained to the wall and unconscious down in the cellar. Turns out he actually is Jacob and the man who’s been posing is Jacob is actually a man called Stumpy Dowd, a notorious criminal. Instead of getting the man out of there right away they sit down in the cellar chained up while he tells the story of what happened.

While they’re hanging around talking and waiting to get caught, they… get caught. Stumpy knocks Nancy unconscious with the butt of his gun. While she’s weak and still semi-conscious he ties her up with the rope. But she remembers being told by a detective visiting her father that it was possible to hold your hand while being bound so as to slip the bonds later. With Nancy’s natural curiosity she got a demo. So she tries to replicate this while Stumpy is tying her up. They have the usual scene where the criminal boasts of his getaway plans and the victims promised retribution and say things like “you fiend” and “you beast”. Jacob leaves them tied up in the cellar to starve to death or whatever and goes off to go re-kidnap Laura Pendleton to get the rest of her jewels.

Considerations - Violence and melodrama:

The 1960 revision tones down both the violence and Nancy’s excitable nature. When 1960 Nancy first sees Jacob in the basement, she is startled but soon composes herself rather than panicking. Stumpy knocks Nancy out with a cane instead of pistol-whipping her. Instead of raging at him and telling him he’s a fiend, she clenches her jaw and just quietly says, "The police will catch up with you in the end".

The Cult of Domesticity – The matchbook:

There’s a whole plot device with Nancy’s dying flashlight and a kerosene lantern she finds. It’s unimportant except for the curious difference in how she happens to have matches in her pocket. 1930 Nancy had a waterproof matchbox left over from her camping trip. Traditionally feminine 1960 Nancy, having been to a summer camp party rather than actually camping, happens to have a souvenir matchbook from the (dinner & dancing & almost romance) hotel, for her matchbook collection. I was going to put this under “dated plot points” because I remember matchbook collecting being a big thing when I was a kid and everybody (except Nancy Drew!) smoked, but I can’t even remember the last time I saw souvenir matchbooks at every hotel, restaurant, and retail store. But apparently, it’s still a thing, even if they’re no longer a common marketing tool. Who knew?

Index of Posts:

ND3.1 1930 Chs 1-3 vs 1960 Chs 1-2

ND3.2 1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

ND3.3 1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

ND3.4 1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

ND3.5 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

ND3.6 1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

ND3.7 1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

3

3

The Bungalow Mystery - update ND3.5

1930 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

These chapters are peak Nancy Drew, with our intrepid heroine engaging in a little breaking and entering in her zeal to solve the mystery. The two versions follow the same rough outline of events, but with considerably different motivations and storytelling style.

1930 Nancy, mulling over the confrontation with Jacob Aborn, decides to get a hotel room on Melrose Lake and wait until after dark to do more investigating.

“At 6 o’clock she went downstairs for dinner. As she sat alone at a small table in one corner of the room, many diners regarded her with interest, for Nancy Drew was an unusually attractive girl, and the prospect of a daring adventure had brought a becoming flush to her cheeks.”

She calls home to let Laura know what she’s up to, overriding Laura’s concerns about her safety (Nancy’s father is still out of town), and adds the safety measure of instructing her to call the police if she’s not home in 24 hours. That night, she drives out to the cottage and sneaks around the perimeter looking for clues, but finding nobody at home, impulsively decides to break in by climbing a trellis up to Laura’s room. Tension ratchets up when Aborn shows up, almost catching Nancy before she can hide herself, but this gives her an opportunity to spy directly on him as he ransacks Laura’s room searching for her jewelry, pulls money out of the safe to fondle and gloat over, and packs suitcases and a bundle of food to go, all while muttering to himself about his plans. He also speaks of himself in third person as “Stumpy”. Nancy thinks that obviously “Stumpy” can only be the name of a nefarious underworld character and is convinced that he’s a horrible criminal that is about to go on the run.

1960 Nancy, as usual, is more deliberate than impulsive and takes pains to stay within legal limits. Planning in advance, she asks Laura for permission to enter the cottage so technically she’s not breaking and entering. She also spends more time on a cover story as an innocent girl on holiday at the resort hotel, hanging out at the beach in her swimsuit, dressing for dinner and listening to music in the ballroom, etc. Prepared-for-Anything Nancy keeps an overnight bag with swimsuit, change of clothes, and toiletries in her convertible, but for some reason doesn’t keep a spare set of batteries for her flashlight or even bother to put fresh batteries in the flashlight before setting off for a snoopy all-nighter.

Considerations:

The differences in the levels of actual or implied violence are again evident in this chapter, as 1930 Nancy wishes that she had her father’s revolver with her, thinking that she may need it at some point during the night’s events, and later sees Aborn arming himself with a weapon described as “gruesome”. The 1960 revision makes no such references.

There are also some amusing moments in the 1930 version that are missing in the revision, when the more impulsive and passionate original Nancy becomes enraged at seeing Jacob Aborn reading Laura’s private correspondence while ransacking her room. “She longed to fly out at him and accuse him face to face” but manages to restrain herself. Original Nancy is also forced to endure the discomfort and tedium of surveillance, cramped and uncomfortable wedged into her hiding spaces and having to wait for long periods of inactivity while Jacob goes through mundane daily activities.

There are no vital dated plot points, but I noticed that the 1930 cottage has no electric lights, as Aborn is carrying an oil lamp around with him as he’s moving through the house, and I was again surprised by a mention of Nancy having to make a long-distance call home, to a town that’s less than 20 miles away.

The Cult of Domesticity:

The mid-century values of true womanhood are in full evidence with these chapters in the 1960 revision, as the author inserts plenty of passages to soften and emphasize femininity and feminine interests that are absent in the original. Laura is all atwitter as she gets ready to go to the barbecue with Don in Nancy’s place. Nancy’s dinner is fully described (steak, baked potato, and tossed salad). The passage I quoted above is almost fully transcribed and inserted into the original, which is a little jarring, as the descriptive style of Mildred A. Wirt Benson contrasts sharply with Harriet Stratemeyer Adam’s utilitarian prose. But Adams expands on Nancy’s attractiveness with a Romance opportunity, when, as she lingers on the porch watching couples dance, a red haired young men began to walk towards Nancy with an invitation in his eyes, but she hastily goes to her room laughing about mixing romance and detective work.

Index of Posts:

ND3.1 1930 Chs 1-3 vs 1960 Chs 1-2

ND3.2 1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

ND3.3 1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

ND3.4 1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

ND3.5 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

ND3.6 1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

ND3.7 1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

ND3.8 1930 Chs 22-25 vs 1960 Ch 18-20

7

7

The Bungalow Mystery - update ND3.4

1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

These chapters are where our teen sleuth gets down to some serious investigation. Her father is still out of town on business, so 1930 Nancy takes off alone to confront Jacob Aborn. Driving along the lane to his lake cottage, she catches a glimpse of him walking through the woods with a small bundle under his arm and sneaks after him until he disappears inside an apparently abandoned old bungalow. She’s undeterred by the posted Keep Off sign. “Nancy studied the warning a trifle uncertainly, and then shrugged her shoulders. ‘I’m not afraid! It will take more than a sign to scare me away!’”

Unfortunately, Aborn comes out while she’s standing on a box and trying to peer through the boarded up window and angrily orders her to go away and stop sneaking around. With remarkable dignity, considering she was actually caught in the act, she warns him that he had gone too far and she would not permit him to call her a sneak thief. Nancy gives him Laura’s letter and Aborn tries to convince her that Laura is unbalanced and just telling wild tales about being mistreated, claiming that she stole valuable jewels from him. Nancy can spot the gaslighting from a mile away and their argument escalates. When Aborn threatens her with a stick, she beats a retreat.

The 1960 revision is similar in essentials, but minimizes or eliminates any violence. Instead of the confrontation between Aborn and Nancy ending with a threatened beating, Nancy tries to trick him into giving away information under the pretense of innocent ignorance, then leaves when he starts getting suspicious.

The revision also adds two extra (unnecessary!) subplots and other drama so that every chapter can end on an artificial cliffhanger. For example, her father forgets his house key and decides to climb in through a window rather than just waking the family up to let him in. Luckily, the police don’t shoot him on sight after Nancy has called to report a burglary in progress. One subplot has Nancy helping her father investigate a bank embezzlement case by doing character checks on various suspects, one of whom will show up again later. The other subplot seems to exist only to reinforce The Cult of Domesticity (details below) but adds another new character: Don Cameron, an old “friend” (who took her to Spring Prom!) happens to be driving by while she’s walking down the street and invites her to a barbecue that week in honor of his sister’s wedding.

Considerations – Nancy’s sleuthing: There’s a more deliberate approach in the 1960 revision than in the original. 1930 Nancy is impulsive and hot-headed, and the writing style puts us more in Nancy’s head, so we are mulling over the clues and her intuitive leaps together with her. 1960 Nancy is equally resourceful and intelligent, but is cool and collected. She takes the time to alter her appearance to present an image of an older, businesslike woman for her sleuthing expedition. She plans ahead for the confrontation with Laura’s guardian, using her letter as a pretext. When he finds her snooping around the bungalow, she probes him with questions designed to catch him lying, rather than just arguing until he finally threatens her with bodily harm.

Dated Plot Points: None, really. I had some thoughts about long distance calls and an enthusiastic description of an ultramodern building that (wow!) had a self-operated elevator with gleaming aluminum doors and carpeting, but I ran out of energy for researching. Are long distance calls even a thing anymore? But it did strike me that I no longer give any thought the cost of calling someone several hundred miles away, when it used to be a financial consideration when you had to call someone in the next town over.

The Cult of Domesticity – Caregiving and meal preparation: There are two pages of descriptions of 1960 Nancy putting together dinner for herself and Hannah complete with description of dinner (chicken casserole, a crisp salad of lettuce and tomatoes marinated with tangy French dressing, and milk), complete with presentation (on trays decorated with doilies, with napkins and silver). Bonus description of Nancy helping get Hannah to bed. Several other meals are described, though not in the same excruciating detail. Breakfast: pancakes, sausage, and fresh squeezed orange juice. Lunch: fresh salad and hot rolls. None of this exists in the 1930 original text – only one meal is alluded to, and Hannah (the servant, not the 1960 motherly housekeeper) does all the preparation and cleanup.

The Cult of Domesticity – Woman’s destiny: The 1960 revision continues to add new elements to introduce the virtues of courtship and marriage. When new character Don Cameron encounters Nancy, their relationship is explained as not just old friends (which is how they interact with one another), but that he had taken Nancy to the Spring Prom, and he promptly asks to take her to a barbecue. More unnecessary background on Don assures the reader that he would be a suitable future mate: educated, hardworking, and able to support a family. Also, another wedding! Don’s sister is getting married, and a few sentences are wasted on Nancy enthusing over it.

1960 Nancy’s modesty is displayed for the reader as she blushes and changes the subject when her father’s secretary (an unmarried woman, naturally, because married women need to be caring for their husbands and households and making babies) tells her how pretty she looks.

Index of Posts:

ND3.1 1930 Chs 1-3 vs 1960 Chs 1-2

ND3.2 1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

ND3.3 1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

ND3.4 1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

ND3.5 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

ND3.6 1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

ND3.7 1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

10

10

If It Bleeds ★★★★☆

Of the four novellas in this collection, the title story is unquestionably the best, and not only because we get to spend more time with Holly Gibney from the The Outsider and the Mr. Mercedes series. It's probably the most complete of the stories. Mr. Harrigan's Phone and The Life of Chuck were classic SK "what if" games for the imagination. The last one, Rat, was not his strongest, but another "being a writer is hard" navel gazer mixed with Faust.

Audiobook via Audible, read by Will Patton, Danny Burstein, and Steven Weber. All do a fine job, but I was delighted to have Patton back and voicing Holly again.

7

7

1

1

The Bungalow Mystery - update ND3.3

1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

1930 Nancy is still struggling to keep her brave little blue roadster going through the storm and the soft muddy dirt road when a small tree, struck by lightning, falls in front of her car and blocking the road. The original text portrays Nancy as intelligent, capable, and determined, but has a sense of humor about her normal human foibles. “The tree was a small one and Nancy thought that two men could move it quite easily. Unfortunately, the two men were not in evidence.” Laura suddenly appears, having run away from the Aborns. She helps Nancy move the tree so she can escape with her to River Heights.

Laura tells Nancy her story once they’re warm and dry at home. Her sob story of mistreatment mostly consists of being made to do housework as Jacob Aborn has no servants, and not being given any money to go shopping with. More disturbing, though, he took her fur coat (she thinks he plans to pawn it) and he’s been trying to get her to turn over custody of her mother’s jewelry to him. Although she thought she had a small fortune of about $60,000 (~$900k today), he tells her that it was poorly invested and she has less than $15,000 (~226k today) left. Her guardian has been locking her in her room (locks on the outside of bedroom doors!) so she was forced to climb out the window to escape. She notes in passing that he sneaks off every night, carrying a small bundle.

Nancy’s father is out of town on business, so they put Laura’s jewelry in the Drews’ wall safe and Laura writes a letter to Jacob Aborn saying that she will not accept him as her guardian and she will not come back. Nancy plans to take him the letter as an excuse to snoop around. She plans to tell him that Laura is staying “with friends” and that she has engaged an attorney.

This episode is where the 1960 version begins deviating significantly from the original. Two new characters – a teenaged brother and sister whose family are coincidentally good friends of the Aborns – drive up while Nancy is trying to move the tree. Laura shows up several chapters later at Nancy’s home. Her story is a little different, limited to the Aborns angrily yelling at her and locking her in the bedroom when she refuses to hand over her jewelry for safekeeping, then overhearing them plotting to get the jewels away from her. I guess 1960 readers might have been less sympathetic of a rich girl being asked to do housework and not given money to go clothes shopping. Unlike the 1930 version, the girls consider going to the police, but decide they need first need hard evidence that the Aborns are thieves.

Considerations – The 1930 driving experience: Two small asides in these chapters illustrated how very different the experience of driving an automobile was in 1930, with respect to power steering and heating systems, especially as there was no mention of it in the 1960 revision. When 1930 Nancy finally got home from her arduous drive back from the lake, the story notes that her arms ached from the strain of holding the car to the road. This would have been tough enough, since she was driving through deep ruts and soft mud for most of the drive, but she was doing it without power steering, which wouldn’t be commercially available in automobiles until two decades later. The 1930 text also noted that both girls were “soaked and chattering with cold” when they got home. Unlike 1960 Nancy, her 1930 original didn’t have the luxury of keeping a plastic raincoat and boots in her car, and although the first interior heaters were introduced in the 1929 Model A using hot air from the engine, they didn’t work very consistently.

Considerations – Hitchhiking: I was at first taken aback that 1960 Laura’s escape included hitchhiking most of the way to Nancy’s house, because the revisions rarely feature nice young ladies engaging in risky behavior, and I dimly associate hitchhiking with hippies. But after a little more thought, I remembered that once upon a time, hitching a ride was a perfectly normal and acceptable way for a person without a vehicle to go places, and I wondered at what point it became associated with risky and/or disreputable behavior. Most sources stated that hitchhiking has mostly declined because it’s now illegal in most states and also just about everyone in America owns a car these days. There was also a focused discouragement campaign starting in the 1970s, through police and media efforts to warn potential ride hitchers and ride givers of stranger danger.

In following hitchhiking links, I was tickled to find a connection to my earlier post about 1960’s beauty salons in a 1971 newspaper blurb about barbers trying to make it illegal for men to have their hair done in a beauty salon. The laws of economics are beautiful – if you refuse to give your customers anything other than a manly buzzcut, they’ll take their business elsewhere. And the 1970s were a glorious decade for men’s hairstyles.

Dated Plot Points – Child protective services: In neither version does anyone consider calling Child Protective Services for Laura, or seem to think it unusual that a 16 year old orphaned girl is travelling alone, booking herself into hotels and making her own transit accommodations. I didn’t find out much about how legal guardians are appointed or how/if they are monitored for the protection of the minor child, but I did get a little history on the evolution of child protective services in the US.

In the early 20th century, protection from neglect and abuse depended primarily on neighbors or family members intervening on behalf of the child and enforcement, if any, came from the police. There were no federal child welfare services until the SSA of 1935. Child labor wasn’t even outlawed until FLSA of 1938, so it wouldn’t have even been criminal for the Aborns to have made 1930 Laura get a full time job in a sweatshop or a coal mine or whatever. Even at the time of the 1960 revision, organized protective services were unavailable or inadequate in most communities. Laws requiring mandatory reporting of child abuse couldn’t even have helped 1960 Laura – they weren’t passed until 1967.

I’m under the impression from my reading that even what services were available were mostly focused on the poor, so perhaps a wealthy orphaned teenager wasn’t considered at risk for even the limited services available.

Index of Posts:

ND3.1 1930 Chs 1-3 vs 1960 Chs 1-2

ND3.2 1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

ND3.3 1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

ND3.4 1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

ND3.5 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

ND3.6 1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

ND3.7 1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

6

6

2

2

The Bungalow Mystery - update ND3.2

1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

In these chapters, the girls get better acquainted, visiting one another and meeting Laura’s suspiciously awful new guardian, before parting ways with Laura going to live with the Aborns and Nancy getting to have another perilous storm adventure while driving home.

In the original 1930 version, Laura visits Nancy and Helen at the girls’ summer camp (vs the 1960 resort motel) the next day, where they get to know one another a little better. Helen brags on all of Nancy’s exploits as an amateur detective. Laura, confessing that she’s still worried about meeting her new guardian the next day, asks Nancy and Helen to visit her at the hotel so she’s not entirely alone with him.

1930 Nancy is thoroughly unimpressed with Laura’s new guardian. Jacob Aborn isn’t ugly, so he’s not immediately recognizable as a ND villain, but the reader, and Nancy, have enough clues. The flashy diamond on his hand, the scowl and cruel glint in his eyes, his boasts about his genius with money, and the plans to take Laura away to a remote cottage on Melrose Lake at an address he refuses to disclose, all put Nancy’s wind up. Once they’re out of sight, Nancy and Helen overhear Jacob yelling at Laura to get packed and quit sniveling.

After an interlude of 1930 Nancy and Helen doing fun girls’ campy things and Nancy teaching Helen to swim, it’s time for Nancy to go home. Her 40 mile drive has plenty of drama, because there are storm clouds in the distance, she’s on dirt roads until she gets close to home, and she come unexpectedly on a detour that takes her off in a mysterious direction. When the storm once more breaks over her in a fury, the rutted dirt roads become so bad that our intrepid girl detective has to stop and put chains on her tires. She ruefully wishes someone would come by and help her, but our intrepid girl detective doesn’t hesitate to get out in the storm and mud and do it herself.

1960 Differences: Once again, the revision complicates the story by adding unnecessary characters and subplots while eliminating the wonderful subtleties and atmosphere of the original. 1960 Nancy has an early encounter with a new character who turns out to be Laura’s guardian’s wife, Marion Aborn, who shows up at the motel looking for help with a flat tire. She’s immediately recognizable as a villain, because she’s rude, swaggering, and mean to the help. Also, she has bleached blonde hair, so villain status confirmed. Nancy, as always, is polite and helpful, and demurely lets Helen angrily rant about Marion’s behavior, because 1960 Nancy is always too virtuous to say mean things, no matter the provocation. Another new character is Helen’s Aunt June, who only exists to feed the subplot of Helen’s marriage and another subplot of Hannah Gruen’s (1930 Nancy’s housekeeper servant and 1960 Nancy’s housekeeper mother substitute) sprained ankle. See Cult of Domesticity below for more on these characters and subplots.

Like the original version, the 1960 revision makes it clear from their descriptions and behavior that the Aborns are suspicious characters. But here we have Jacob Aborn confiding to the girls that Laura is actually penniless because her mother blew all their money with her prolonged illness and their lavish lifestyle. Helen recognizes Jacob as a man who almost ran them off the road earlier in a black foreign car, and in another new subplot, Nancy spends a great deal of time unsuccessfully trying to connect him with that foreign car.

The stormy drive scene is similar, except that 1960 Nancy doesn’t need chains on her tires. I guess automobile and tire technology has advanced enough to make it unnecessary, even when driving on a dirt road detour?

Considerations – Property Insurance: When 1960 Nancy explains to the motel manager about his boat ending on the bottom of the lake, he tells her not to worry about it, because the insurance will cover it. 1930 Nancy’s apologies are similarly dismissed by the campground owner, but insurance isn’t even mentioned. I was curious about the difference, so here is what I was able to find out: Insurance was largely unregulated at the time of the original text, with rampant fraud and abuse. Companies began self regulating for fear of government takeover after the Social Security Act in 1935, but there was still no federal regulatory oversight until 1944. So it’s possible that property insurance simply wasn’t commonly carried by a small business like the girls’ summer camp in 1930.

Considerations – The Beauty Parlor: The 1960 Laura was able to sneak away and visit the girls because Marion Aborn was having her hair set at the beauty parlor. I remember thinking how amusingly archaic my grandmother was, going to have her hair set in the early 1980’s, but when I read this, I was unsure at what point a weekly wash and set stopped being a regular thing. In looking for the answer, I was amazed to read that some salons still have regular customers for this. For you youngsters who have even less memory of this bizarre hair ritual than I do, here’s an explanation that matches my mother’s stories, including the disgusting scalp buildup underneath a week’s worth of ratted hair coated in Dippity Do and layers of Aqua Net. Also, I found a YouTube newsreel short of a “beatnik” transformation into a “gracious lady” (looking 10 years older IMO) and a slideshow of 1960 beauty salons.

Considerations – Villains: Ugly, tacky, rude people are always the villains in the Nancy Drew worldview. Especially vulgarly dressed and made up women. This is convenient as it makes them easy to spot.

The Cult of Domesticity: Once again a driving force in the 1960 revision. The added subplot of Helen’s impending marriage is the most obvious example, giving the girls page time to dream over wedding plans and dress designs. We also get a new character in Aunt June, who of course works as a department store buyer and only appears in a single chapter to drive two new subplots that seem to exist only to further the Cult of Domesticity theme: marriage and caregiving. These will appear as new story elements in the revised text, apparently only to help Nancy seem more traditionally feminine.

Dated Plot Points – the Perilous Drive Home: A modern retelling of this story would have to do some serious gymnastics to make this work. This scene depended on Nancy not having access to a weather forecast, a weather app, a maps app showing road closures, or a mobile phone to call AAA/Roadside Assistance. The dirt (not even gravel!) roads are still possible, but unlikely. Even in the revision where the dirt road is only a detour, I think it unlikely that a detour from an area where there are fine hotels and lake resorts to a major urban center like River Heights is going to be re-routed on a badly maintained dirt road. Dirt roads, (in my experience) are fairly uncommon today, at least in rural Texas. They are mostly private roads or small short roads that lead only to private property or residential areas.

Dated Plot Points – the Black Foreign Car: I couldn’t understand why the author created the foreign car subplot. Clearly the car is going to be a clue or plot twist in the revised story later, but why the emphasis on “foreign”? Some internet sleuthing later, I discovered that the first imported automobiles arrived in the US in 1949, and by 1960 would have been widely available, but still uncommon enough to catch the attention of an observant person. I’m still not sure why the sinister overtones by virtue of its foreignness, but the driver being recklessly rude and endangering other drivers was enough to mark it as a story villain in the Nancy Drew worldview.

Index of Posts:

ND3.1 1930 Chs 1-3 vs 1960 Chs 1-2

ND3.2 1930 Chs 4-6 vs 1960 Ch 3

ND3.3 1930 Chs 7-9 vs 1960 Chs 4&8

ND3.4 1930 Chs 9-11 vs 1960 Ch 5-7; 9-10

ND3.5 Chs 12-14 vs 1960 Ch 11-12

ND3.6 1930 Chs 14-17 vs 1960 Ch 13-14

ND3.7 1930 Chs 18-21 vs 1960 Ch 15-17

9

9

2

2

Putting some books aside and ready to tackle old projects

As I finished the first short story in the Chekhov book, I realized that I needed to make a decision about my Art of Reading project. It sounds kind of silly, but I just skated through my English courses in school and my major was in the sciences, so I've always felt that I'm not getting enough from my reading. I took this course on audio, with the idea that it might make me a more thoughtful reviewer (it didn't because I'm a lazy reviewer) and that it might enhance my pleasure in my fiction reading (it did because I'm now more engaged with the writing).

Anyway, I had compiled a list of the books used to illustrate the principles taught in the course, and was determined to read them all, being mindful of how they were used as examples of writing techniques. It helped because most of them are classic lit that I have yet to read. Chekhov's The Lady with the Dog was one of these, but further down the reading list. I really need to start with Bleak House. So I'm reshelving Chekhov, and will start sprinkling in my AoR books into my regular random Book Genie selections, but doing them in order of the lessons.

My other project has been languishing for over a year. Nancy Drew has been shamefully neglected, so I spent the morning picking up on where I left off in The Bungalow Mystery and will start posting those installments today.

11

11

2

2

Mary Wakefield ★★★☆☆

I don't think I've ever read a romance where I found both romantic leads so thoroughly boring. I had no interest in seeing whether they would work it out, was even sort of rooting for the devious and catty rival Muriel to knock Mary aside and snatch the indolent Philip away. And most likely make him miserable for the rest of his life. The charm of this book was in the peripheral characters and in the strong sense of place. Perhaps my favorite character was Phillip's half-grown spaniel pup, with his melodramatic moanings and joyful gambolings and callow slinkings and mournful mopings.

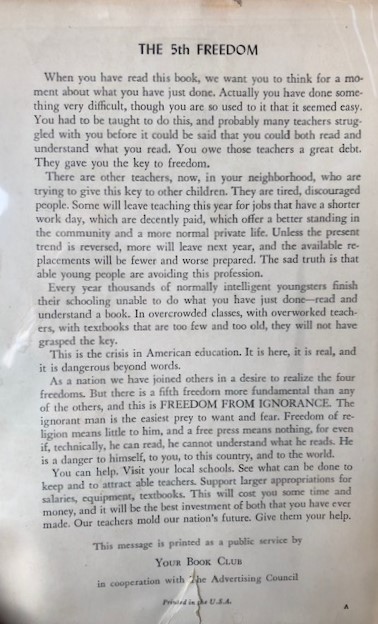

Hardcover, third in a series, in which I have no desire to read further. I inherited this vintage 1949 book from my father, as one of the few mementos of his mother. I never met her, but from his accounts she was a loving and terrifyingly Sicilian lady who, with her cabal of equally terrifying sisters, kept all the rascally extended family in line.

The book itself has some interesting features. I love vintage books. The yellowed and unevenly cut pages. The wonderful smell of musty old libraries. But this one also has the hardcover embossed with a leafy logo, the original price sticker from what used to be a fancy Austin downtown department store, and a delightful rant about teachers and public schools on the back cover. Also, I used one of my favorite old bookmarks, a fundraiser for The Wilderness Society, with a photo of a solitary live oak in a field of bluebonnets and Indian blankets. It is so very Central Texas that it always makes my heart ache a little.

7

7

4

4

If It Bleeds - 76%

"I love you, Mom," Holly says and ends the call. Is that true? Yes. It's liking that got lost, and love without liking is like a chain with a manacle at each end.

Oh how this struck me. It is so painfully true.

2

2

2

2

Mary Wakefield - 133/337 pg

Really Mrs. Lacey had cause for concern. There was her elderly husband dancing like a sailor on the lower deck, with a young woman only partially clothed, and there was one daughter out in the darkness with dear knows whom, and the other daughter brazenly flirting with a divorced man.

1

1

2

2